La mandoline connaît un âge d’or dans la seconde moitié du 18ème siècle, tout particulièrement à Paris entre les années 1750 et 1790. Quelles sont les raisons de ce succès? La réponse se trouve certainement en une conjonction de différents éléments.

Tout d’abord, le 18ème siècle voit l’arrivée à Paris de nombreuses troupes de théâtre et de musiciens italiens qui s’y produisent à l’occasion des foires (Saint-Germain et Saint-Laurent) et qui favorisent l’introduction et le développement d’un nouveau style en France. En 1752, les représentations de l’opéra bouffe La servante maîtresse de Pergolèse déclenchent la querelle des Bouffons, affrontement entre les défenseurs du goût français et les partisans du nouveau goût italien.

À cette époque, la mandoline connaît un grand succès en Italie (en particulier à Naples) où elle est utilisée en tant qu’instrument d’accompagnement de la voix lors de sérénades : « Cet instrument est très brillant, il est charmant la nuit pour exprimer le douloureux martyre des amants sous les fenêtres d’une maîtresse. En Italie et en Espagne on n’entend la nuit que des guitares et des mandolines jouer des notturno »1. Cette tradition n’échappe pas à d’illustres compositeurs tels que Mozart, Grétry ou encore Paisiello qui l’utilisent sous cette forme dans leurs opéras respectifs Don Giovanni (1787), L’Amant Jaloux (1778) et le Barbier de Séville (1782). Mais à la même époque la mandoline était aussi utilisée comme instrument soliste et virtuose, ce dont témoignent les nombreux concerti écrits par des compositeurs napolitains, parmi lesquels Carlo Cecere, Emanuele Barbella, Nicolo Conforto.

En France, des concerts s’adressant à un nouveau public apparaissent dans le cadre des salons ou des associations développant, notamment dans la bourgeoisie, un intérêt pour un répertoire nouveau et pour des formations de musique de chambre ou pour des instruments adaptés à ces nouveaux lieux plus intimes. Il faut aussi associer la recherche d’un certain exotisme à un intérêt pour les instruments rares comme la mandoline, la guitare, la musette ou la vielle à roue par exemple. Parmi ces nouvelles structures, on peut citer le Concert Spirituel, fondé à Paris en 1725 par Anne Danican Philidor, dont les activités devaient se poursuivre au palais des Tuileries jusqu’en 1790 et où le premier mandoliniste à se produire fut Carlo Sodi en 1750, suivi de Giovanni Cifolelli et Gabriele Leone en avril et juin 1760.

Enfin, le succès du style galant (ou rococo), dans sa quête d’une musique plus divertissante, plus simple, qui privilégie l’art de l’ornement plutôt que celui du développement, cristallise les influences et les éléments qui permettent à la mandoline de s’inscrire, au sein du répertoire savant, dans ce nouveau paysage musical.

Cet engouement pour la mandoline et pour la musique italienne attire en France et à Paris de nombreux maîtres de mandoline italiens qui viennent y jouer leurs compositions mais aussi enseigner l’instrument aux enfants de la noblesse (notamment aux jeunes filles).

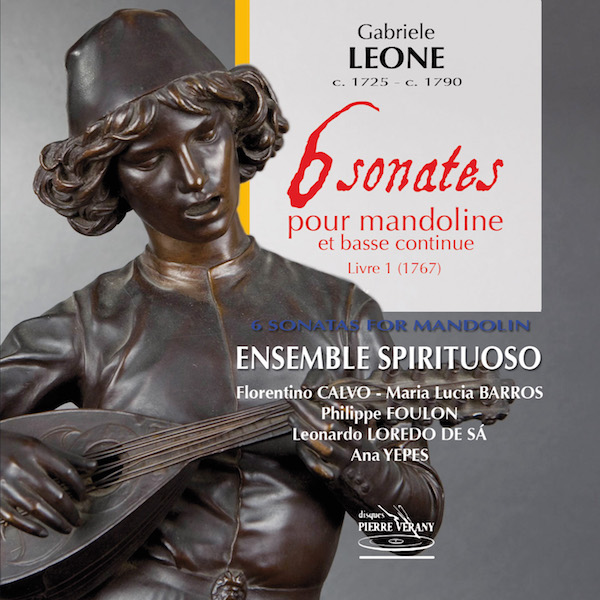

Gabriele Leone (c. 1725 – c. 1790)

Il est certainement le plus illustre des mandolinistes de son époque. Il se produit à plusieurs reprises au Concert spirituel puis devient impresario du directeur de l’Opéra de Londres. De retour à Paris, il est maître de mandoline du duc de Chartres (futur Philippe Égalité) à qui il dédie en 1768 sa Méthode raisonnée pour mandoline, ouvrage de référence en ce qui concerne la technique instrumentale de l’époque. Mais Gabriele Leone reste un personnage mystérieux dont on ne possède que très peu d’éléments biographiques. C’est finalement sa musique (dont le style et l’écriture se caractérisent par une grande virtuosité instrumentale, des mouvements lents expressifs, des recherches d’effets contrastés, souvent comiques) qui nous révèle le caractère de ce personnage haut en couleur.

Le premier recueil de six sonates pour mandoline et basse (publié en 1767 à Paris et dédié au Baron de Bagge) contient la quintessence de son art. Il constitue sans aucun doute l’un des joyaux du répertoire pour mandoline de la seconde moitié du 18ème siècle. De la sonate d’introduction jusqu’au feu d’artifice de la dernière, Léone dessine par petites touches successives les paysages contrastés et colorés d’un itinéraire pittoresque.

« Il faut remarquer que la mandoline et le cistre ne sont jamais mieux accompagnés que par le clavecin et la Viole d’Orphée »2

«Les Italiens méprisent les chiffres; la partition même leur est peu nécessaire; la promptitude et la finesse de leur oreille y supplée»3.

C’est en s’inspirant de ces recommandations et avec un effectif instrumental étoffé et Inédit (mandoline, clavecin, viole d’Orphée ou violoncelle d’amour, guitare baroque et castagnettes), que l’ensemble Spirituoso, initialement composé de mandoline et clavecin pour son premier enregistrement La Mandoline Baroque (PV712061), part à la rencontre de Gabriele Leone, appelé aussi Leone l’Espagnol.

Florentino Calvo & Maria Lucia Barros

In English:

The second half of the 18th century witnessed the golden age of the mandolin, especially in Paris between 1750 and 1790. But what accounts for this popularity? No doubt the answer lies in a convergence of different elements.

First of all, numerous theatre groups and musicians were arriving in Paris from Italy to perform at local fairs, such as Saint-Germain and Saint-Laurent, which encouraged the development of a new musical style in France. In 1752, a performance of Pergolese’s opera buffa The Servant Mistress unleashed the Querelle des bouffons, between those who were defending the French taste and those who preferred the new Italian style.

At this time, the mandolin was already extremely popular in Italy (especially Naples) where it was used to accompany vocal serenades. According to the 1772 preface of Michel Corrette’s Method: « The instrument has a bright sound, and at night, played beneath the mistress window, it offers a charming expression of the pain endured by lovers. In Italy and Spain, the night air is filled with guitars and mandolins playing notturnos. »

Composers like Mozart, Grétry and Paisiello used the mandolin to the same effect in Don Giovanni (1787), L’Amant Jaloux (1778) and the Barber of Seville (1782), respectively. The instrument was also used for solo and virtuoso performance, as evidenced in the many concertos written by Neapolitan composers, including Carlo Cecere, Emanuele Barbella, and Nicolo Conforto.

Meanwhile, in France, an eager public began to frequent the bourgeois salons and clubs where this more intimate kind of music was well served by chamber ensembles and instruments adapted to the new setting and repertoire, particularly appreciated by the bourgeoisie. A taste for exoticism probably also played a role in the mandolin’s popularity, as it did for the guitar, the bagpipe and the hurdy-gurdy. Among the new societies was the Concert Spirituel, founded in Paris in 1725 by Anne Danican Philidor, which continued to perform at the Tuileries Palace until 1790. Carlo Sodi was the first mandolinist to play with the ensemble, in 1750, followed by Giovanni Cifolelli and Gabriele Leone in April and June of 1760.

In the end, the gallant (or rococo) style, with its search for a musical form that would amuse, one that was simpler and favoured the art of ornamentation over thematic development, came to dominate the musical landscape. Bringing together all the various strands of influence, it succeeded in positioning the mandolin firmly within the classical repertoire.

Such was the public’s appetite for Italian music and for the mandolin that a number of Italian masters travelled to France; they not only performed their compositions, but also taught the children of the nobility (especially the girls) how to play the mandolin.

GABRIELE LEONE

(ca 1725 – ca 1790)

Leone was undoubtedly the most illustrious mandolinist of his day. He performed at the Concert Spirituel and then served as impresario at the London Opera. Returning to Paris, he was named Mandolin Master for the Duc de Chartres (future Philippe Égalité) to whom he dedicated his 1768 mandolin Method, acknowledged as the book of reference at that time for instrumental technique. Nonetheless, Gabriele Leone remains a mysterious figure, as little biographical information has survived. Rather it is his music – characterized by a grand virtuoso style, expressive slow movements, a search for contrasting and sometimes comical effects – that provides the most vivid and colourful portrait of the man.

His first book of six sonatas for mandolin and bass, published in Paris in 1767 and dedicated to the Baron de Bagge, encapsulates the essence of his art. It marks a highpoint in the mandolin repertoire of the late 18th century. From the opening sonata to the fiery last one, Leone traces a picturesque musical path which, by successive strokes, paints a landscape rich in contrasts and colour.

In the 1772 preface to his Method (a quick guide for learning to play the mandolin), Corrette wrote: « It must be said that there are no better instruments for accompanying the mandolin or the cittern than the harpsichord or the viole d’Orphée. »

And according to Jean-Philippe Rameau in his Erreurs sur la musique dans l’Encyclopédie, 1756-1757: The Italians scorn figured notation; they don’t even need a score; instead they rely on a quick and refined ear.

Inspired by these references, the Spirituoso Ensemble, originally composed of just mandolin and harpsichord for its first recording, La Mandoline Baroque (PV712061), has now expanded to include the viole d’Orphée, the violoncello d’amore, baroque guitar and castagnettes as well. With this enhanced instrumentation, our Ensemble is ready to explore the work of Gabriele Leone, also known as Leone the Spaniard.

Florentino Calvo & Maria Lucia Barros

English translation : Alison Clayson

1 Préface de la méthode de Michel Corrette «pour apprendre à jouer en très peu de temps la mandoline», 1772.

2Ibidem

3Jean-Philippe Rameau, Erreurs sur la musique dans l’Encyclopédie, 1756-1757